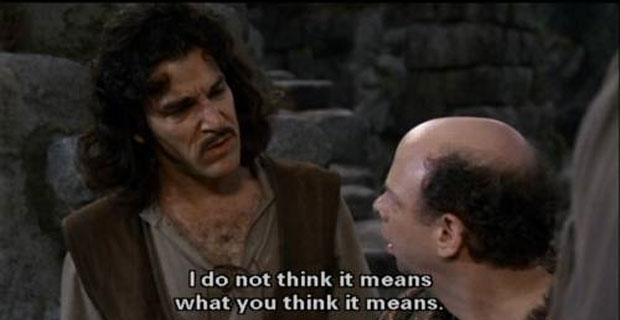

Words. They’re like tiny nuggets of enriched uranium. They hold great power and potential energy, but they’re also extremely fragile and unstable. When harnessed correctly, they can galvanize people behind a concept; when handled sloppily, they’re likely to blow up in your face. Despite the potential fallout, humans continue to rely on words as their primary currency for information exchange.

“Immersion?” “Compelling?” The overuse and misuse of these terms and others in videogame discourse has led to a grand muddying of the waters. The different factors and variables that go into either of those concepts are legion, but the words themselves strangely become vague placeholders that somehow magically absolve the writer from describing what specifically about a game drew them in or transported them to that other world (i.e. doing their job). As such, we end up with lazy writers and confused readers.

The abuse of words and phrases like “immersion” has thankfully seen a decline in recent days. But, like a game of linguistic Whack-a-Mole, there’s always a new idiotic rodent in dire need of flattening. Our target for the sweet hammer of logic today? “Trial and error”.

The most frequent misuse of the term seems to be concentrated in the discussion of platformers, where you’ll find it sprinkled liberally like salt and pepper on a piece of grossly over-cooked chicken. Reviews, critiques, and comments of games in this genre have been getting it wrong for years. From classic franchises like Mega Man and Rayman to modern indie titles like Braid or P.B. Winterbottom, you’ll inevitably find a gripe that summons the phrase “trial and error”.

I actually read a review of Limbo that said the game “suffered from a reliance on trial-and-error gameplay.” If you take a closer look at the meaning of the term, the absurdity of that statement becomes more apparent. A game cannot suffer from trial-and-error gameplay, because trial and error is a fundamental component of gameplay. There is no other kind.

All games employ trial and error. Trial is interactivity — providing the player with a set of tools/options and an environment to play with them in. Error is defining the rules — determining what actions result in success and which lead to fail states. There is no game that doesn’t utilize this system; rhythm games, shooters, and even artsy-fartsy titles like Passage employ it (in Passage every playthrough technically results in a fail state: death).

Essentially, saying that a game suffers from trial and error gameplay is no different in meaning from saying that a game suffers from being a game. If games were self-aware, that would be a very cool nihilistic meta-statement to make. Since they aren’t self-aware (yet), it’s just wrong. Telling developers that their games are bad due to trial and error gives them absolutely no substantive or constructive information with which to push the quality of their games forward.

When a writer uses this term in the context of game critique, it generally indicates a lack of ability to accurately zero in and elaborate on the source of their dissatisfaction. I’ve misused the phrase myself recently in an attempt to use the accepted meaning of the term rather than the actual meaning. No more. Particularly because there is no accepted meaning. It’s all about context.

When someone dings Mega Man for trial and error, what they usually mean is that they are frustrated with the difficulty level or that they feel the game relies too heavily on pattern memorization. When Demon’s Souls was slammed for trial-and-error gameplay, it wasn’t just the difficulty that reviewers were concerned with, but also the steep penalty for hitting a fail state. In the case of Limbo, the penalty for a fail state is minimal, so many reviewers used the term to refer to their concern that the conditions for success aren’t more implicity communicated (i.e. if you die even once and it’s not your fault, it’s always bad design).

If you’re familiar with the game in question, it’s possible to work backwards and make an educated guess as to what they mean by that phrase. But asking a reader who is coming to a review or editorial without having played the game to try and properly infer which meaning of trial and error the author intended is simply bad writing. It does nothing to inform the audience or strengthen the dialogue.

I personally think part of the problem is that really drilling down to that level of detail exposes the subjectivity of the craft involved in game writing. Games writers are not the arbiters of objective quality when it comes to things like trial and error.

We can say, “this game has massive bugs, therefore it is a bad game.” However, it is not our job to say, “this game is extremely difficult (or easy), therefore it is a bad (or good) game.” It is our job to say, “I enjoyed this title in part because it possesses x level of difficulty, and that meshes well with my tastes.”

It is the readers’ job then to plug their own tastes into the equation and base their own decisions accordingly. The writer acts as a compass needle; based on how the writer’s opinion, style, and reasoning resonate with a given reader, that reader can then use the point to chart a course either towards or away from the writer’s stance. When a writer relies on an ambiguous catch-all phrase like “trial and error,” the needle becomes wobbly and therefore a less valuable tool to the reader. It’s asking an audience to adopt an opinion based on faith rather than specific reasoning, and the Internet’s not so good at that.

Avoiding “trial and error” outside of its actual meaning can only elevate the quality of videogame discourse. It will force us as writers to bring more specificity and logic to our arguments, and that will provide us with much more benefit as readers. And by that, I mean it will make game analysis more immersive and compelling.

Published: Aug 30, 2010 04:00 pm