Yippe ki yay, monster trucker

Licensed video games have always been like the interior of an abandoned barn. Sometimes you might find a long-abandoned car that is in dire need of restoration, but more likely, it’s just full of spiders. Die Hard on NES is neither of those things. It’s more like finding a long-abandoned lunar lander in an old barn. You wonder how it got there and if it’s a good idea to try it out.

It’s an absolutely bizarre game that transcends the discussion of whether it’s good or crap. It’s fascinating. The design is something that isn’t exactly without comparison, but the way it functions is out of this world.

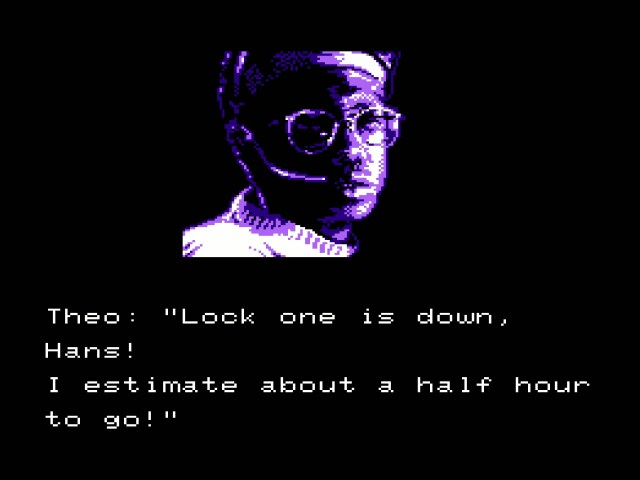

Haaaaans!

I’d recommend watching Die Hard before playing this game. While knowing the movie is rarely needed for playing the licensed game, it’s practically required for Die Hard. There is some setup – terrorists have taken over Nakatomi Plaza and are breaking through locks to get at money – but it doesn’t really go into depth as to what your goals are or how to accomplish them. It doesn’t explain the existence of a “foot” meter, only viewable in the pause menu. Likewise, you won’t be prepared when the game intentionally tricks you at the end.

It will also help if you read the manual. It goes over all the rules that aren’t otherwise explained. Like, if you go into the vents, you’ll drop your machine gun. There’s nothing within the game that indicates that you will. You aren’t asked if you want to drop your weapon. You’ll just emerge from the vents and realize that you’ve been stripped to your pistol.

It’s a strangely literal interpretation of the movie. There is a set number of “crooks” dwelling within Nakatomi Plaza, and pretty much the only solid objective in Die Hard is to take them all out. In order to take on Hans Gruber, you need to kill all the enemies before he’ll unlock the door. However, there are various ways to make it easy on yourself, such as taking out the computer on the 4th floor to delay the terrorists. Everything aside from removing the terrorists is optional.

The monkey in the wrench

Die Hard plays in real-time. Upon beginning, the terrorists start working their way through the locks in the vault, and you’re fighting the clock to take as many out before then. Once the vault is broken, everyone moves onto the 30th floor, meaning the more that are left, the more you’re going to have to fight there and then before you’ll be able to take on Hans. There’s a counter on the pause menu, letting you know how many are left. Don’t take too long, or Hans will escape.

In a lot of ways, Die Hard on NES is an extremely early example of an immersive sim. You’re dropped into a world with a bunch of rules and little scripting beyond those rules, and it’s up to you to figure it all out. The only thing linear about Die Hard is the march of time and the related placement of events.

It also uses systems such as “fog of war” which obscures areas that your character cannot see at that moment. Terrorists hidden behind corners are obscured in darkness. The aiming system takes some getting used to, as it isn’t simply four or eight-directional but works a bit like a dial. If you can’t get a handle on it, spraying and praying is a reasonable strategy. There are also multiple ways to get around the floors, including stairs, an elevator, and the vents. The terrorists will respond to your disruptions, with Hans telling them to check floors where you’ve created a ruckus. This allows you to avoid or ambush as you see fit.

Welcome to the party, pal

What is going to frustrate many players is the fact that Die Hard is obviously designed to take multiple attempts to complete. It’s not a very long game, but it is an unforgiving one. It’s entirely possible for you to make a minor miscalculation at the very end of the game and have to start over completely. This wasn’t too uncommon at the time – Contra was similarly brutal about making you start over – but it’s something that hasn’t aged well.

What makes the repetition a little harder to swallow is that Die Hard is a rather small game in general. Consisting of the small handful of floors in Nakatomi Plaza and the few dozen thugs that live there, it sort of feels like it needs two more movies worth of content to call it a complete package. That’s a bit understandable when you consider there’s only one person in the credits listed under a creative role: Tony Van. Almost certainly, he wasn’t the only developer working on Die Hard. He’s not listed as a programmer anywhere else. However, if we choose to believe this was a solo dev effort, that’s damned impressive!

With no disrespect to Tony Van (he did have a hand in my beloved Shadowrun for Genesis), it’s most likely more of a case that Activision didn’t credit people, or they simply didn’t want to be associated. Junichi Saito has, at the very least, been identified as the composer. Oh, hey! He did the music to Predator on the NES! The only decent part of that game!

Now I have a machine gun, Ho-Ho-Ho

As I said so long ago, I don’t really care to wonder if Die Hard is truly kusoge. Its design is just out of this world. It feels like something we wouldn’t truly get until years later. It may be short, perhaps it relies too much on outside sources to actually understand it, and it might have been better suited to a more advanced console, but that’s not the point. Die Hard pushes 8-bit design. It’s art born from its constraints.

Unfortunately, being a licensed game, it’s not likely to be ported. An NES cartridge with Die Hard living on it will run you well north of a hundo. That’s possibly due to it being a late release for the console in 1991. This year, give the gift of Die Hard on the NES. Watch the light in the eyes of people who discover this non-linear proto-immersive sim for the first time. After all, that’s what Christmas is all about.

For previous Weekly Kusoge, check this link!

Published: Dec 18, 2022 10:00 am