Hello darkness, my old friend

I’m entirely cut off from the world. Noise-canceling headphones cover my ears, the lights in my room are switched off, and I’ve thrown a sheet over my curtains so that not one speck of light will appear from the street lights outside. And I’m shaking.

A film of sweat covers my mouse, and I can still taste the blood in my mouth — the result of a bitten lip during a particularly intense game of cat and mouse in a pitch-black, waterlogged basement. I’m a hot mess.

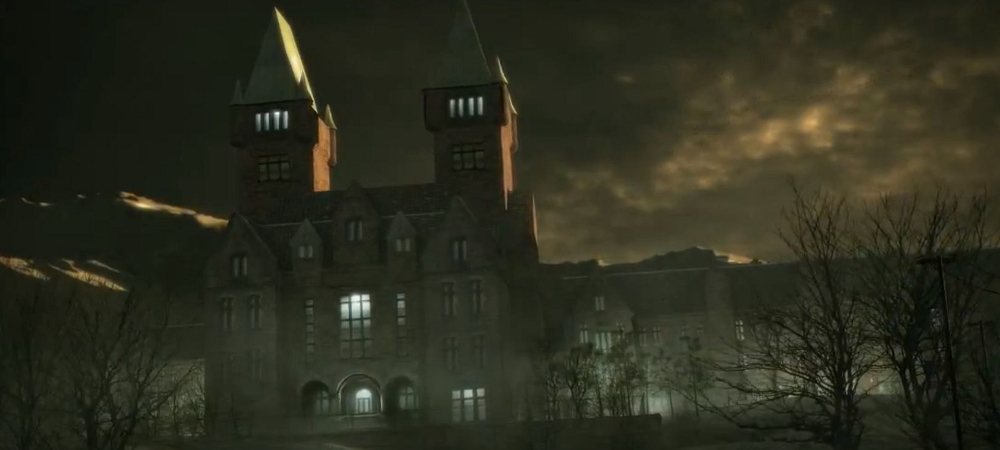

Outlast is not a fun game. It is a game of cruel limitations with an oppressive, constantly unsettling atmosphere. Its goal is to terrify; to tap into deep-seated fears of imprisonment, impotence, and horrors lurking in the darkness.

I’ve got the light on now. I don’t think I’ll be turning it off again.

Outlast (PC [reviewed], PlayStation 4)

Developer: Red Barrels

Publisher: Red Barrels

Release: September 4, 2013

MSRP: $19.99

Rig: Intel i5-3570K @3.40 GHz, 8 GB of RAM, GeForce GTX 670, and Windows 7 64-bit

There’s something deeply invigorating about horror. Being scared increases awareness and focus; everything becomes more intense. That being the case, I’m in the throes of the horror equivalent of a cocaine high at the moment.

Every time I put down Outlast, leaving the world of survival horror and the rundown Mount Massive Asylum for the more mundane world, and stop being investigative journalist Miles Upshur, I’d smoke a cigarette and pour myself a glass of whisky. These are two things that I enjoy immensely normally, but after an hour or so of running down dark corridors, evading psychopathic, deformed monstrosities, and screaming like a wee lassie, the dram of peaty nectar and stick of slowly burning tobacco and carcinogens seemed like a care package from God.

I want to write about how Outlast is a lot like Amnesia, but I’m hesitant to do so, because — despite the obvious parallels like the genre, first-person perspective, and lack of combat — they both manage to tread such different ground even though they have clear, surface similarities.

Outlast is loud. Explosions, screams, roars, smashing glass, and nerve-shattering music that starts off quiet — all you can hear is Miles’ breathing and whimpering — and then builds up to a deafening crescendo filling ears and rattling bones. When it’s silent, it’s a trap. Something awful is about to happen, and the game takes almost no time at all to teach you that. But then sometimes nothing will happen, because Outlast is also treacherous and untrustworthy.

Matching its volume is its graphic nature. There’s gaudiness in how grotesque it is. The disfigured things that you’ll be confronted with are stomach-churning, because they look almost like normal people, until you realize that they are humanoid canvases of scabs, scars, gaping wounds, and surgical fuck-ups. And everywhere there is blood and viscera, smeared on the floor, clinging to the walls.

Red Barrels, the obviously disturbed developer, is showing off. It’s hiding decapitated heads in toilets, it’s forcing you to crawl through a sewer tunnel filled with shit to escape a seven-foot-tall hulking behemoth, and it’s throwing cadavers at you when you open doors.

Gaudy, loud, and shocking — Outlast revels in being these things, but what elevates it, what differentiates it from jump-scare horror like Dead Space, for example, is its surprising subtlety. There’s nuance amid all the noise and violence; a welcome juxtaposition that plays with expectations and works towards making the title excellently paced.

There’s the way that Outlast slowly reveals the history of Mount Massive through documents like patient files and descriptions of experiments. You’re not simply fleeing monsters, you’re a journalist, investigating a corrupt Asylum, following a lead. There are moments of quiet exploration, hunting down clues, where there’s nary a ferocious, stalking creature in sight.

And then there’s the subversion of videogame limitations. Typically, especially in first-person games, you’re free to fight and usually shoot anything threatening, empowered by guns and fists, but then when anything important happens, you’re artificially locked in place. Your view becomes fixed, your feet become encased in concrete, or sign posts slap you on the head.

Outlast turns this on its head. Instead, there’s no fighting. Your only chance to survive when confronted by an enemy is fleeing, hiding — under a bed, in a cupboard, or just in the darkness — and praying that nothing finds you. But there’re none of the artificial shackles found that are found in the, arguably, less limited first-person titles. Despite the fact that the game’s job is to scare the bejesus out of you, you’re free to look away, miss something horrifying, and not spot that shadow moving erratically at the end of the corridor.

When you do lose that freedom, it’s because someone has literally taken it away from you — not because the game has wrested control from you. You’re strapped to a chair, you’re drugged, you’re being gripped by massive hands before being flung out of a window.

I’ve mentioned the first-person perspective a bit already, and I do hope you’ll forgive me if I bring it up again. It’s just that Outlast exploits it so masterfully that it demands emphasis. It’s not merely the perspective itself, but rather all the things that accompany it. It’s not enough to force players to look through the eyes — not hampered by a HUD — of a trapped journalist, Outlast makes you feel like you are in Miles’ body.

When you crouch, the camera isn’t just lowered. There’s a slight wobble, and when you look down, there’s Miles’ hand — your hand — tentatively sticking out, just in case you fall. And when you give up all pretense of stealth and just make a break for it, running, fleeing, desperately attempting to find some way to escape your pursuers, you shake, you bounce, and it’s frenetic.

Mirror’s Edge, oddly, springs to mind when I consider the movement and physicality. Especially when I found myself dragging my exhausted body into an air vent or climbing over objects. There’s a sense that effort is being expended, even though it’s mechanically very smooth.

Absent firearms — or weapons of any kind — only one tool is available: a trusty camcorder. It’s essential, because the night vision feature is a life-saver. Although it’s a tool used to assist, it’s also the source of a lot of Outlast‘s most horrifying moments. Night vision chews through the camera’s batteries, so you’ve always got to be on the look out for more juice. The device always seems to run out at the most inopportune moments, leaving you vulnerable, surrounded by impenetrable darkness, even if just for a few seconds.

Not only a light to guide your path, the camera also gives you a distinct advantage over most enemies. When there’s nowhere to hide, a dark room or the end of a poorly lit corridor is almost as good as a locker. With night vision on, you can see your pursuer hunt for you, but he can’t see you. He can feel you, though, and he can hear you.

Individually, the stealth, movement, camera, and music are all excellent, but it’s when they are combined to create a perfect horror scene that Outlast truly becomes something special. Imagine: you’re crouched in the corner of a room, shrouded in darkness. The chains of insane, wailing patients, trapped in their beds, rattle. A mad doctor is hunting you down, and he knows you’re in the room — he just doesn’t know where.

He turns to face you, the night vision giving his eyes a demonic glow, but has he spotted you? Or is he just looking in your direction? The music is quiet, atmospheric, but there’s a screechy undercurrent hinting at terrible things to come. The doctor moves towards you, sharpening his knives as he mutters.

It’s all too much. You’re a nervous wreck. You stand up, and just run. The music explodes, all manic strings and booming horns, as you bolt through corridors, frantically looking over your shoulder, flinging closed doors behind you and pushing cabinets up against them, leaping over beds and drawers, until you can find a cupboard to cower in or get far away enough from the doctor so that you can breath easy, at least for a moment.

Then there’s a banging on the door, the wood splinters, and a knife appears. He’s laughing now, the mad doctor. You weren’t safe. You’re never safe in Outlast. And the chase begins anew. It’s exhausting and horrible and it’s absolutely wonderful.

While such chases are great, my most memorable experience saw me take on the role of Pavlov’s dog. I found myself outside, soaked from rain, and tightly wound. The camera was rendered almost useless outdoors, and I was running through thickets and trees, utterly lost. Occasionally lightning would strike, and I’d see something awful, but maybe it was just a statue.

As I made my way from a fountain, that I initially believed was a giant monster, to another building, the music sprang to life, and howls ripped through the noise of the rain. I couldn’t see anything, I could only hear. I’d been trained well, though, and heart in mouth, I bounded around looking for escape, screaming “no, no, no” until my flatmate had to come in and see if I was okay. I’ll never know if there was anything behind me.

It is only if you get caught that the impending doom reveals itself to be something of an illusion. Should one of the savage denizens of Mount Massive get their mitts on you, they’ll do one of two things: grab and throw you, giving you an opportunity to escape, or hit you until you run away. You’re given so many chances before you actually die, that fear of death is possibly the least prominent fear in the entire game.

Yet this is, perhaps, a rather accurate portrayal of horror. It’s the chase and the torment, not death, that really inspires discomfort and terror. In game terms, death merely means you end up at an earlier point, and this time without the shocks and surprises.

Outlast simultaneously reminds me of the grainy slasher flicks of the ’70s, the gruesome body horror of Clive Barker, and gratuitous modern torture porn. It manages to squeeze a great deal of diversity into what is quite a small package of around six or seven hours, but it doesn’t burst or struggle to reconcile the different elements.

When I finished my journey through Mount Massive, a wave of relief washed over me. I was free from the asylum, able to turn on the lights, take off my headphones, and not jump every time I saw a shadow. But as I soaked away in the bath, washing off the sweat and stench of fear, I heard the floor creak. It sounded just like the old floorboards in the asylum. I knew it was just my flatmate wandering about, but I couldn’t help looking at the door, expecting to see a knife, and I wondered if I could fit my flabby, naked body through the tiny window of my bathroom, and just leg it down the street.

Published: Sep 4, 2013 02:00 pm