Stay in the light

When people look back upon the great horror games of this year, they’re probably going to forget about White Night, and that’s understandable. It doesn’t break any ground, it isn’t littered with jump scares to draw in the YouTube crowd, and its gameplay lacks depth.

It’s also one of the better composed horror stories in games over the last few years, assuming you don’t mind that being the only real reason to show up.

White Night (PC, PS4 [reviewed], Xbox One)

Developer: OSome Studio

Publisher: Activision

Released: March 3, 2015

MSRP: $14.99

Set near Boston in the latter years of the Great Depression, White Night tells a pulp horror tale with noir trappings. Driven off road in a storm by the ghostly form of a woman, the player begins wounded at the gates of decrepit Vesper mansion, home of a once powerful family with a grim legacy. What begins as a simple effort to make it through the night develops into an exploration of the Vesper family and how it connects to the apparition which drew the player in.

Storytelling is the major aspect of White Night, and the one which it most capably succeeds at. As the player explores, they’ll find dozens of journal entries, notes, photos, bits of private correspondence, and newspaper clippings relating to the Vespers. Walls are covered with family portraits and art, most of which can be examined and rarely see their descriptions recycled (though the art occasionally is). Narrative creeps in at the corners, these expository bits gradually developing into a fascinating tale of gloom, desperation, and madness. They’re wonderful, and encourage a thorough exploration of every room. Voice-acted narration from the protagonist comes in at points as well, though these are typically far less interesting and hindered a bit by a youthful voice which doesn’t seem to match the character.

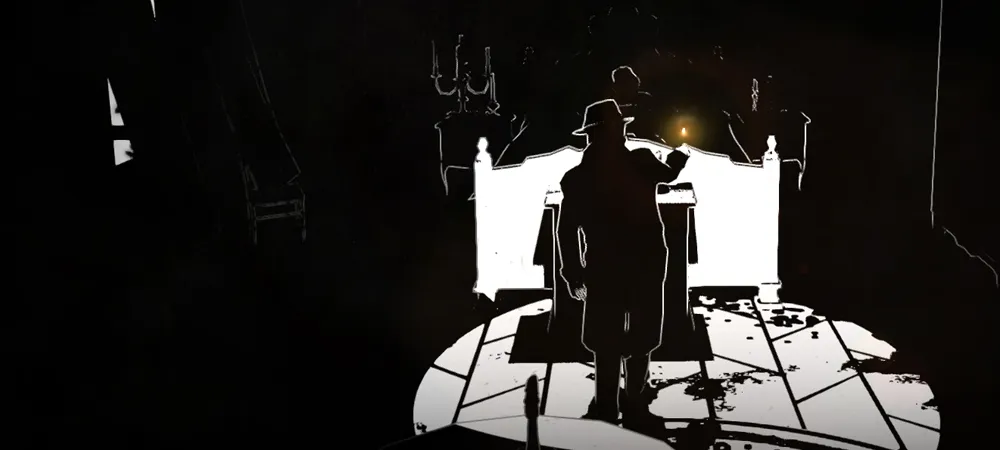

Taking an unusual approach to visual design, the game is presented in 3D, using fixed camera angles, almost exclusively in black and white. Stark and captivating, the sharp contrast and its limitations effectively draw the eye to details and discrepancies. The darkness is oppressive and encroaching, yet often preferable to the light which reveals that there actually are horrible things in hiding. It’s a stylish look that well serves play dominated by object collection and interaction, as the player’s view is often limited to their immediate vicinity. This, paired with the fixed cameras, is occasionally disorienting, as landmarks which could be used to identify the player’s relative position are rendered invisible in the dark, which does make the experience more intense (albeit at the risk of frustration).

Light and darkness are used literally and metaphorically throughout the game as core concepts. The player is helpless in the dark, unable to interact with the environment in any meaningful way. Inside the mansion, as working light fixtures are few and far between, the player must rely on matches for light. A maximum of twelve matches can be carried at one time, and the length of time they burn is affected by factors like movement, making it hard to gauge how much time one has, and (as anyone who’s been down to a few matches will tell you) they’re unreliable. There is a little thrill to be had from running dangerously low, only to have two matches in a row come up as duds.

As time is spent out of the light, thrumming bass begins to build in volume and add a layer of frantic intensity which is exciting. Refills of matches are plentiful, however, and the amount of time the player has to actually spend in the dark before succumbing to it is considerable. One could play so poorly that victory becomes impossible, but the likelihood of this happening unintentionally seems low.

The use of matches for light also hinders the player’s ability to interact with objects which require the use of both hands, making most puzzles in the game follow a pattern of finding the objective, then finding a light source which allows for interaction with the objective, which may then lead to another puzzle. Most puzzles aren’t difficult to solve, requiring just a touch of logical deduction based on easily found clues.

If the player is struggling, they can reference an in-game hint system that collects observations the player has made and puts them a newspaper layout which usually points out what may have been overlooked. Occasionally, the protagonist will chime in with a comment of their own which indicates where they should check next. These features do a good job of cutting down fruitless wandering to find the next goal without explicit hand holding.

The real killers are the ghostly forms of the Vesper family matriarch. Found in almost every room of the mansion at some point, these spirits roam about or obstruct progress and give chase when they see the player. If caught, the game is immediately over, which occasionally feels a tad unreasonable in light of the fixed cameras, but it does make their presence something to be feared and being hunted by them provides some tense moments. Ghosts can be evaded, usually by exiting the room they occupy or by getting a bit of distance in darkness (they’re blind, a fact the game fails to point out until halfway through). They can also be destroyed with electric light, and a considerable percentage of the player’s time will be spent figuring out how to turn on lights just to kill ghosts in their path.

White Night bills itself as “survival” horror, a case made on the basis of its loose extrapolation of mechanics found in other games attributed to that genre. Players expecting a traditional survival experience of limited resources against considerable odds will likely find it underwhelming. Very rarely is a significant challenge presented, save for a few larger rooms with a lot of ghosts to avoid (easily overcome with a little persistence, though the trial and error can be wearisome). Limited resources, while still limited, are plentiful and widely distributed. Save points, though not numerous, are placed well to minimize the distance between them and any point of major interest. The trappings of survival horror are there, but there is no teeth to the gameplay.

It would be more accurate to say that White Night is an exploration adventure, an interactive story in the “weird tale” tradition. Just enough obstacles exist to make that story feel as though it was earned, that the player participated in the telling, but conveying the story is the priority. From clever exploitation of gameplay mechanics to the pages and pages of rich exposition which carefully unravel and the moody jazz soundtrack, everything exists in service to the fiction. In that, it succeeds, and it’s a story worth experiencing and deserving of praise.

[This review is based on a retail build of the game provided by the publisher.]

Published: Mar 11, 2015 10:00 am